Making Sense of the Beatitudes

The Beatitudes are some of Jesus’ most famous and beloved words. Yet we can brush them off in a pious but dismissive way. In piety, we revere them, but how often do we take them seriously, as if they truly applied to our lives today?

As the Second Vatican Council proclaims, Jesus teaches us fully what it means to be human. Jesus is the answer to the question that is every human life. In truth, this is on display in the beatitudes, which foreshadow Jesus’ life and the truth of discipleship. In the words of St. John Paul II, the Beatitudes are “a self-portrait of Christ and … are invitations to discipleship and communion” (Veritatis Splendor 16).

Each of the beatitudes begins with the Greek word makarios, which is often translated “blessed” or “happy.” We should take note of their traditional title—Beatitudes, which perhaps ironically suggests that herein lies the path to true happiness, or beatitude. In this vein, some scholars suggest that a better translation of the Greek word might be “flourishing,” such that the beatitudes would read: “Flourishing are the poor in spirit,” etc.

Human flourishing is closely tied to virtue in the classical tradition, as found in the writings of Plato, Aristotle, and St. Thomas Aquinas. Here, the ethical life is not merely about external deeds but a journey toward becoming a certain kind of person, a process of the full flowering of human nature—of living the fully human life. This full-flowering of human life is simultaneously about living in accordance with truth, justice, and the moral virtues and attaining happiness, since the latter comes about through the objective perfecting of our human nature, as opposed to more modern notions of happiness as mere subjective contentment. For, in the classical sense, happiness is ultimately the fruit of one’s character.

The Beatitudes and the Spiritual Life

Blessed [or flourishing] are the poor in spirit. The first beatitude is traditionally tied to humility. In fact, in the lectionary, this passage is paired with Zephaniah 2:3 and 3:12, both of which emphasize humility as the character of the authentic people of God. Humility is the bedrock of the spiritual life: coming face to face with our brokenness—our true poverty—is precisely what allows the divine physician to enter into the deepest crevices of our hearts.

As many of the saints have insisted, what produces sanctity is not just to “will it.” Rather, the saints generally point in two directions: (1) the importance of recognizing our brokenness; and (2) taking seriously the infinite mercy of God. If we only think about the former—our brokenness—we can despair. But if we only focus on the latter—God’s mercy—we can fall into presumption. The combination of both inclines us toward the Lord in our weakness, but it does so with a filial boldness—childlike confidence in the Father’s love and mercy.

This dynamic is at play in the second beatitude as well.

Blessed are those who mourn. “Mourning” here is associated with sadness over our sin. Commenting on this passage, Pope Benedict XVI describes two kinds of mourning—one exemplified in Peter, the other in Judas. Both men betrayed Jesus, but they differ in what happened afterward. In the face of Peter’s brokenness, he experiences the “healing tears” of repentance, while Judas falls tragically into despair. Benedict writes:

There are two kinds of mourning. The first is the kind that has lost hope, that has become mistrustful of love and of truth, and that therefore eats away and destroys man from within. But there is also the mourning occasioned by the shattering encounter with truth, which leads man to undergo conversion and to resist evil. This mourning heals, because it teaches man to hope and to love again. Judas is an example of the first kind of mourning: Struck with horror at his own fall, he no longer dares to hope and hangs himself in despair. Peter is an example of the second kind: Struck by the Lord’s gaze, he bursts into healing tears that plow up the soil of his soul. He begins anew and is himself renewed.

Jesus of Nazareth, vol. I, p. 86, emphasis added

The link between the first two beatitudes then is this: In seeing our poverty of spirit, our brokenness, we “mourn” over the reality of our sin. But in confidence we turn to the Lord for healing and transformation; and in the Holy Spirit—in the Father’s love—we find true comfort (see Matthew 5:4).

Blessed are the meek. This beatitude alludes to Psalm 37:11, where the “meek shall inherit the land” (the words used in both the Hebrew and Greek original texts mean “land” and “earth”). The Hebrew word for “meek” here is anawim, which refers to the faithful and humble of ancient Israel—it is a word that captures the righteous remnant, the people of God as God desires them to become. In this sense, Mary quintessentially embodies the anawim, as is manifest in her Magnificat (see Luke 1:46-55). And Jesus of course is later said to be “gentle” [here using the same Greek word translated as “meek” in Matthew 5:5] and “lowly” (see Matthew 11:29).

Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness. Our physical hunger is a sign that points to a deeper hunger. Hunger reveals that we are not self-sufficient; we are creatures, in need of God and others. Our physical hunger, then, is a sign of our deep spiritual longing for the Infinite, for God. We all worship something. We need only look at how we spend our time, money, and mental and emotional energy. There are some things we simply will not “miss”—things we continually make time for. This beatitude beckons us to discern the movements of our heart and foster a deep yearning for what truly matters. Only by rightly ordering our desires at the deepest level will we ever truly be “satisfied” (see Matthew 5:6).

In the next three beatitudes, we begin to see how authentic love of God produces genuine love of neighbor.

Blessed are the merciful. Merciful people have received God’s love and forgiveness; they saw their brokenness and came to the divine physician. After coming to grips with their weakness and their deep need for grace, they now have a posture of love and mercy toward others. They pity—rather than condemn—the sinner. Nonetheless, merciful people still call sinners to a higher standard because they know that sin leads to sadness; it destroys our lives and wrecks any possibility of true and lasting happiness.

In being conformed to the image of God, the forgiven sinner images divine mercy for others. In fact, this seems to be a condition for full entrance into the kingdom: “Forgive us our trespasses as we have forgiven those who trespass against us” (see also 18:23-35).

Blessed are the pure in heart. In the Bible, the “heart” is the core of a person—it is our “unified center,” a combination of intellect and will. The “heart” in the Bible is not a reference to our feelings or sentiment. The “pure” in heart are undivided in heart. Subsequent passages in the Sermon on the Mount track closely with this idea. For example, in Matthew 6:22 we read about a “sound eye.” The word translated here as “sound” is haplous, which is sometimes taken either as “healthy” (hence “sound”) or “generous.” The two ideas actually come together: First, the “eye” in Jewish tradition is connected to greed—an evil eye sees things it wants and covets them. Second, this saying is sandwiched between two passages dealing directly with money and treasure: Matthew 6:21 (“where your treasure is, there will your heart be also”) and Matthew 6:24 (“No one can serve two masters … you cannot serve God and mammon [referring to wealth]”).

In other words, the “sound eye” is both healthy and generous because this person is attached to the right things in an undivided way. They are seeking first the kingdom(see Matthew 6:33). And this is precisely what Jesus means when he says, “Be perfect as your heavenly Father is perfect” (Matthew 5:48). The Greek word here for “perfect” is teleios, a word that has deep resonance in the virtue tradition, referring to that full “flourishing” of human nature mentioned above. The Hebrew roots behind this idea refer to being “complete” or “whole.” The pure in heart are undivided because they anchor their lives on God and thereby live with integrity or wholeness—becoming “perfect” in that sense, for they have now found healing in the Lord and have come to rest in him. Conversely, the divided in heart are anxious, the opposite of the “wholeness” or “completeness” mentioned above (see Matthew 6:25-34).

Blessed are the peacemakers. Those who are “complete” in the Lord find peace—and become sources of peace for others. “Peace” here is not merely the absence of conflict, but what St. Augustine describes as the “tranquility of order” (see CCC 2304). Peace is the fruit of an undivided life.

Since the reward of the eighth beatitude is the same as the first (“for theirs is the kingdom of heaven,” see Matthew 5:3, 10), some consider the Beatitudes better enumerated as seven, as opposed to eight. If we consider this last one an eighth beatitude (“Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake”), we should see in it the fact that the Christian life is always an imitation of Christ; as St. Paul puts it, we are “conformed” to the image of Christ (Romans 8:29). In fact, the Christian life is ultimately a matter of Jesus’ life being reproduced in us (see Galatians 2:20).

Hopefully, we can learn to see the Beatitudes not as lofty but unattainable aphorisms but as the heart and soul of the Christian life. Indeed, the Beatitudes enable and empower us to live the truly human life by bringing about genuine human flourishing, both on a natural and supernatural level. For grace does not abolish or destroy nature but builds upon it—that is, grace heals, perfects, and elevates our fallen human nature.

How can we make the Beatitudes real in our lives today?

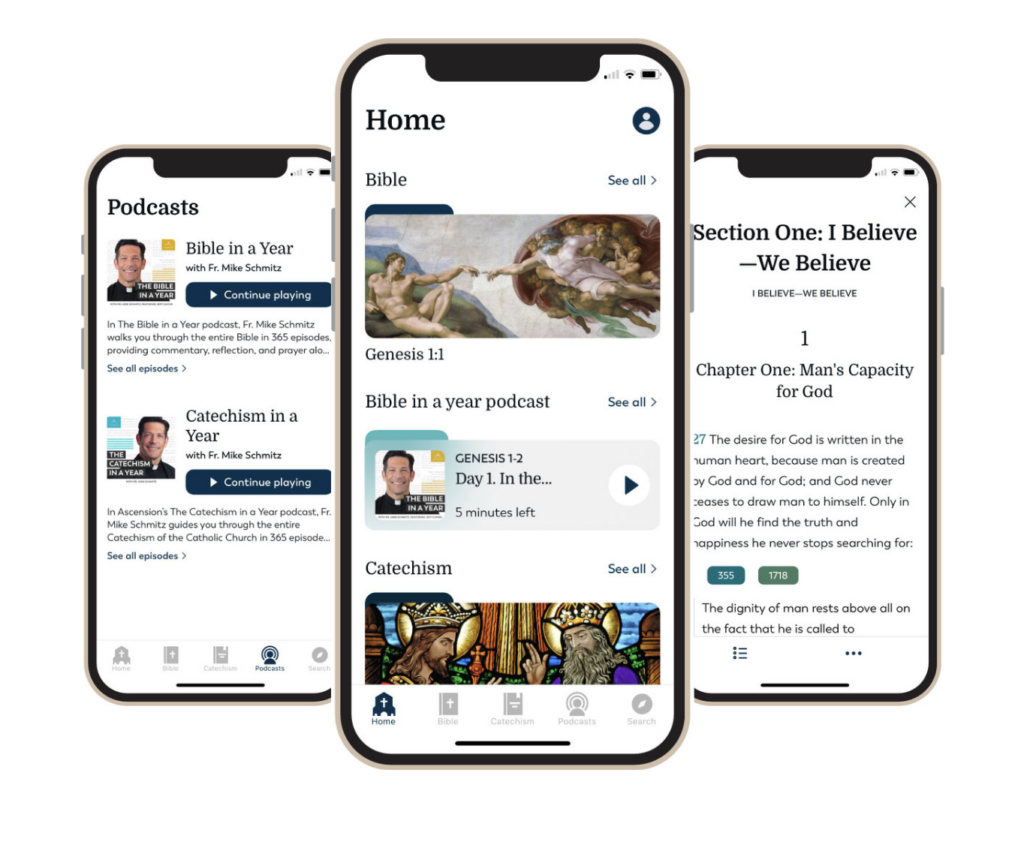

It’s Here: The Bible & Catechism App!

The word of God and the complete teachings of the Catholic Church. Answers and commentary by Fr. Mike Schmitz, Jeff Cavins, and other experts. Video, audio, and textual commentary. Right on your phone.

You May Also Like:

Does God Really Expect Us to Be Perfect?

How to Keep Your Focus on Jesus [CFR Video]

Ten Life-Transforming Truths

Dr. Andrew Swafford is associate professor of theology at Benedictine College. He is general editor and contributor to The Great Adventure Catholic Bible published by Ascension, presenter of the Bible study Romans: The Gospel of Salvation (and author of the companion book), also by Ascension, and presenter of Hebrews: The New and Eternal Covenant Bible study. Andrew is author of Nature and Grace, John Paul II to Aristotle and Back Again, and Spiritual Survival in the Modern World. He holds a doctorate in sacred theology from the University of St. Mary of the Lake and a master’s degree in Old Testament & Semitic Languages from Trinity Evangelical Divinity School. He is member of the Society of Biblical Literature, Academy of Catholic Theology, and a senior fellow at the St. Paul Center for Biblical Theology. He lives with his wife Sarah and their five children in Atchison, Kansas. Follow him on Twitter: @andrew_swafford.

I needed a really good explanation of the Beatitudes. I came to the right place.

I needed this explanation of the beatitudes, also. Very well done. I’ve never heard such a useful description.

These words on the Beatitudes by Dr Swafford are amazing! The Holy Spirit always leads me to exactly what I need to hear in my heart.