It is remarkable how much things have changed in just, say, fifteen years. In fact, the issue of gender identity has really come to the forefront in the last couple of years, particularly since the 2015 Bruce (now “Caitlyn”) Jenner interview.

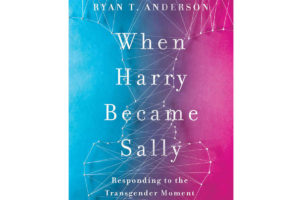

Ryan T. Anderson has done the Church (and the culture at large) an immense service with his book When Harry Became Sally: Responding to the Transgender Moment, giving us a thoughtful, well-reasoned, and informative treatment of transgender issues.

Ryan T. Anderson has done the Church (and the culture at large) an immense service with his book When Harry Became Sally: Responding to the Transgender Moment, giving us a thoughtful, well-reasoned, and informative treatment of transgender issues.

First, he recognizes that the average person who struggles with gender dysphoria (a feeling of discomfort with one’s biological sex) is not the same as a transgender activist; that is, his book is aimed at helping those who struggle with this dysphoria (as well as informing those who might minister and care for them) by at least making clear that there are alternatives other than transitioning to the other sex.

In fact, in explaining why he wrote the book, Anderson says:

“The simple answer is that I couldn’t shake from my mind the stories of people who had detransitioned [people who transitioned to the opposite sex through hormones and surgery, and then subsequently sought to return to their biological sex]. They are heartbreaking. I had to do what I could to prevent more people from suffering the same way” (Anderson 2018, 205).

He does weigh in with serious arguments, but these should not be considered as directed at those who struggle with gender identity, but rather aimed to inform all those concerned—e.g., parents and caretakers of transgender children, as well as other parents, and to point the way toward commonsense approaches to public policy.

Is This Really Not Hurting Anyone?

Perhaps the most devastating part of his book is chapter three, where detransitioners tell their stories. Common to a number of these stories is the following pattern: they felt pressured to transition, as if this were the only option (one wonders here whether ideological agenda overrode sincere care for what was best for the patient); medical professionals often didn’t pursue the underlying psychological issues that may have led to their gender dysphoria; they now express regret, particularly over lost fertility and irreversible side effects; and many detransitioners now feel they were way too young at the time to have made such life-altering decisions.

Cari’s Story

One such story is that of a woman named Cari. She transitioned socially at age fifteen (switching to male clothing, pronouns, etc.) and started taking testosterone at seventeen. Her family and community were very welcoming and accepting of the change (ibid., 52-3). But by age twenty-two, she detransitioned back to her biological sex as female.

Looking back, she now recognizes some of the reasons that led to her dysphoria, such as “feelings of inferiority for being female” and “depression” (ibid., 54). But she recounts that none of these issues were addressed when she went to gender therapists:

“The truth is that a lot of women don’t feel like they have options. There isn’t a whole lot of place in society for women who are like this, women who don’t fit, women who don’t comply. When you go to a therapist and tell them you have those kinds of feelings, they don’t tell you that it’s okay to be butch, to be gender nonconforming, to not like men, to not like the way men treat you. They don’t tell you there are other women who feel like they don’t belong, that they don’t feel like they know how to be women. They don’t tell you any of that. They [just] tell you about testosterone” (ibid., 53).

One can hear the sadness in Cari’s voice when she says:

“This is the real outcome of transition. I’m a real live 22-year-old woman with a scarred chest [from a mastectomy, i.e., a surgery to remove her breasts] and a broken voice and 5 o’clock shadow because I couldn’t face the idea of growing up to be a woman. That’s my reality” (ibid., 56).

Cari sums up the peculiar and tragic nature of hers and like stories with the following question: “I want to ask you, how many other medical conditions are there where you can walk into the doctor’s office, tell them you have a certain condition, which has no objective test, which can be caused by trauma or mental health issues … and receive life-altering medications on your say-so?” (ibid., 53).

“TWT’s” Story

Another story is that of a man going by “TWT,” who transitioned at nineteen and then detransitioned at thirty-nine. He recounts how as a child he was physically small and slow but very bright academically—which made him a bit of a misfit with his fellow boys, who then subjected him to intense bullying (ibid., 63). Eventually, he came to identify with the girls with whom he seemed to have much more in common. When he went to a therapist with these feelings, the bullying wasn’t addressed and he was put on estrogen after only two visits:

“I went to the clinic and told the psychologist my story and that I wanted to be female. I didn’t talk about bullying and I was unaware that it was related in any way. This is something I sorted out later when I was in real therapy” (ibid., 64).

“Crash’s” Story

Another young woman going by “Crash” transitioned at eighteen and began testosterone treatment at twenty. Looking back on her story, she notes that trauma (her mother committed suicide right around this time) and a misogynistic culture contributed to her dysphoria (ibid., 59).

In other words, she disliked the way women were treated—and subconsciously thought life would be more palatable if she were a man; and then with the added trauma of her mother’s death, transition became a way to cope. Anderson cites several extended quotations from her which are worth reading but are too long to quote here (ibid., 60-1). But perhaps most telling is Crash’s open letter which she penned after an activist attacked detransitioners for sharing their stories. Crash writes:

“Transitioning was all about trying to get away from what hurt us and detransitioning is finally facing that and overcoming it. It’s about making connections between how other people have treated us and how we’ve seen ourselves and our bodies. It’s about remembering terrible, scary, upsetting memories and integrating them. It’s about making sense of what happened, giving up old explanations that no longer work …. In the process we often reject much of what we believed when we were trans because it no longer suits us or seems true. It’s about understanding how the society around us has influenced us and shaped how we thought, felt and came to view ourselves …. Detransitioning is learning to accept and be fully present in your body …. [C]hanging my body did not get at my root problems, it only obscured them further. My actual problems were trauma and hating myself for being a woman and a lesbian” (ibid., 75-6).

Activists Treatment Plan

Anderson explains how activists are pushing to implement treatments at a very young age. If the child’s self-identification with the opposite sex is “consistent, persistent, and insistent,” then social transition can begin as young as Kindergarten (starting with a change to the opposite sex’s wardrobe, use of pronouns, etc.). By age eight or nine, the child is put on puberty blockers, which delay and suppress normal pubescent development. By age sixteen, cross-sex hormones are introduced (testosterone for biological girls and estrogen for biological boys); then by age eighteen, one undergoes sex reassignment surgery (ibid., 120-1).

Anderson explains how activists are pushing to implement treatments at a very young age. If the child’s self-identification with the opposite sex is “consistent, persistent, and insistent,” then social transition can begin as young as Kindergarten (starting with a change to the opposite sex’s wardrobe, use of pronouns, etc.). By age eight or nine, the child is put on puberty blockers, which delay and suppress normal pubescent development. By age sixteen, cross-sex hormones are introduced (testosterone for biological girls and estrogen for biological boys); then by age eighteen, one undergoes sex reassignment surgery (ibid., 120-1).

There are a number of questions we could raise here, but perhaps the first and most basic is whether it’s wise to make such life-altering decisions simply on the say-so of a child? Would we allow children to make such serious and life-changing decisions—before they even hit middle school—in any other area of life?

Further, Anderson cites studies showing that eighty to ninety-five percent of children struggling with gender dysphoria eventually return to identifying with their biological sex, if they are not otherwise prodded (ibid., 123). But putting a child on the above protocol assumes that we know (based on their say-so) which children will persist in their transgendered identity (ibid., 121).

While activists claim that the above program is completely reversible, it’s at least an open question as to what long-term effects there will be from taking puberty-suppressant drugs—not to mention the fact that one’s peers who are not taking such drugs will develop normally, thereby reinforcing the child’s perception of being more and more out of place (ibid., 120-32).

Lastly, such a protocol assumes that we should not attend first to the psychological issues that may be latent (e.g., bullying, trauma), but rather should simply seek to alter the body—in order to align it with the young patient’s self-perception of their “true” gender (a perception which may well not persist, as Anderson notes above).

A Matter of First Principles

From a Christian and a Catholic point of view (and from the vantage point of sound realist philosophy), we have to say that our body is integral to who and what we are. The reason we are pro-life is because when the individual human organism comes to be, the person comes to be. When I bump into a table, I don’t say, “Oops, my body hit the table,” but “I hit the table.”

This whole transgender discussion is reminiscent of the ancient Gnostics, who believed that material reality was evil and that only the spiritual was good—in which case, there is a radical difference between me and my body (in fact, in this view, I’m basically “trapped” in my body). For this reason, in some circles, it didn’t matter what I did with my body—because my body was seen as disconnected from my real (spiritual) self.

Catholics, on the other hand, have always understood that the body and soul form a unity—I am one thing, not two. Consequently, my “self” is not trapped in my body. Therefore, once again, my body is integral to who and what I am. As a consequence, it cannot be the case, for example, that a woman is trapped inside a man’s body or vice versa—for who I am is intimately and essentially connected to my body (ibid., 105).

Now, some activists will point to brain studies, suggesting that we can detect a female brain in a man’s body or vice-versa. Such a postulate dramatically overstates the case. But even were this to be the case, Anderson brilliantly points to the well-known reality of “neuroplasticity,” which refers to the way in which the brain rewires itself based on our behavior. What this means, then, is that a brain study cannot show whether a particular brain state is the cause or the effect of one’s transgender identity. In other words, it is quite possible that when someone identifies with and transitions to the opposite sex, their brain adapts and changes itself accordingly (ibid., 107).

The Anorexia Analogy

With any other dysphoria, where one’s feelings are at odds with physical reality we seek to treat the underlying psychological issues. In other words, if an exceptionally thin young woman came to a doctor with an eating disorder—no matter how convinced she was that she is really fat and overweight—the very last thing the doctor would do is indulge her self-perception and accept it as reality. We could not fathom the repulsion we would feel if this doctor were to prescribe diet pills—or liposuction for her. We would be outraged.

But in essence, that’s exactly what the transgender movement is asking us to do: we’re taking a young person’s “inner feelings” as the determining factor of reality; and not only are we countenancing such a seemingly delusional self-perception, we are seeking to alter their bodies accordingly by way of drugs and surgery—hence, the analogy with diet pills and liposuction (ibid., 96-7).

Moving Toward a Remedy

What Anderson notices and deftly discusses is how we need to strike a virtuous mean on the issue of gender. In other words, in a number of detransition stories, we have a situation where one was beholden to very rigid and fixed stereo-types regarding what it means to be a man or a woman (e.g., men are strong, tough, and aggressive; women are docile, dainty, and submissive); and when the child perceived that he or she didn’t fit these rigid stereotypes, the child began to wonder if perhaps he or she were in the wrong body.

But in reality, just because a boy is sensitive and likes to read doesn’t mean he’s a girl; and just because a girl likes sports and rough and tumble play doesn’t mean she’s really a boy.

We need to teach a virtuous mean between those, on the one hand, who would see “male” and “female” as simply socially constructed categories that have no objective basis in the natural and biological order; and those on the other hand who would identify gender stereotypes as eternal and unchanging realities (ibid., 156). The truth is in between: gender has an objective, biological basis; but the way in which that objective and ontological reality is socially manifested is open to a wide and legitimate variety.

In other words, we need to teach the reality of “male and female he created them” (Genesis 1:27), as something God-given and natural, while at the same time explain that there are many ways of authentically expressing masculinity and femininity—that is, there are many ways of living out the objective and God-given reality of our biological sex.

Policy in the Interest of All

Anderson goes out of his way to emphasize that those who struggle with gender dysphoria need to be treated with compassion, and he notes that where appropriate reasonable accommodations should be made (ibid., 202). But he recounts how President Obama sought to broaden Title IX legislation by transforming its ban on sex discrimination into a ban on “gender identity” discrimination—with the result that one could now use whatever public facilities one desired (e.g., bathrooms, locker rooms, women’s shelters), regardless of one’s biological sex (ibid., 175-6). But this raises serious questions, particularly, for women and girls regarding safety and privacy.

It’s not that those who identify as transgender are more likely to commit sex crimes, take indecent pictures, or expose themselves. Rather, the danger is that other predators will now be able to abuse such gender identity policies in order to gain easier access to victims—in public restrooms, women’s shelters, etc. Such a situation also makes it more difficult to prove criminal intent, since such persons (e.g., a biological male identifying as a woman) could now claim a “right” to be in, say, a women’s bathroom (ibid., 181-90).

This state of affairs is especially difficult for women and girls who have survived rape or other abuse at the hands of males: for such a person, the mere thought that a biological male could walk through the doors of a women’s restroom or locker room is enough to induce anxiety and panic (ibid., 184-5).

And then there is the issue of meaningful equality—for if “female” is a category so loose as to no longer be restricted to biological women, then equality starts to lose its force. For example, in sports, is it really fair for a biological male who identifies as female to compete against other women? Or, is it fair for a female who has been taking testosterone for several months or even years to compete against other women who haven’t been taking such drugs? (ibid., 190-1).

Sex and Gender

At the end of the day, the issue is the “radical claim that feelings determine reality” (ibid., 48, emphasis added). Transgender activists no longer identify transgender as being internally at variance with one’s biological sex, but rather as a person who is internally at variance with their “sex assigned at birth” (ibid., 33). The phrase “sex assigned at birth” is particularly troublesome—since it suggests that one’s biological sex is arbitrarily imposed from without, as if it were no longer a natural reality flowing from a human being’s particular nature.

Alasdair McIntrye, in a famous book After Virtue has a well-known a chapter entitled “Aristotle or Nietzsche?” His point is that this is really the basic philosophical decision: Aristotle represents the tradition of realism—the view that reality is real and objective and is knowable, making the intellectual task one of conforming the mind to reality. Nietzsche, on the hand, represents the view that our wills simply decide and create “truth” as we go along, a view made famous in his phrase “will to power,” as well as in the title of his book, Beyond Good and Evil—the idea being that the will creates moral truth as it goes along and so is thereby beyond good and evil.

This is really the issue: to what extent will our thinking be unmoored from the natural order, and to what extent will the sheer act of one’s will determine what is real? To what extent will our medical practice be grounded in the objective order with a clear sense of what is normal and objectively good for the patient? Or, on the other hand, will we treat medicine as simply a matter of satisfying the patient’s desires, however discordant they might be with reality—as if the patient were merely an economic consumer?

Of course, there are some hard cases, for example, with mixed sexual chromosomes and even genitalia. But such cases are about one in five thousand (ibid., 88). Importantly, such cases are not what drive this debate:

“Most people with a DSD [Disorder of Sexual Development] do not identify as transgender, and most people who do identify as transgender do not have a DSD” (ibid., 92).

The Objective Order of Things

As Aristotle noted long ago, nature and the natural order is what happens “always or for the most part”—for example, eyes are for seeing, even though some people happen to be born blind. But we don’t thereby suggest that blindness is a normal condition. We recognize that a word is misspelled because we know how it’s supposed to be spelled. Similarly, we recognize a disorder by our knowledge of how a thing is rightly ordered. But if we have forfeited our sense of the objective order of things, we will no longer be in a position to speak of disorders—which is precisely the predicament in which we currently find ourselves (ibid., 91-2).

The fact is “sex” is only scientifically and philosophical intelligible in relation to reproduction. We have different sexes, male and female, in order to reproduce—that is, “male” and “female” are necessarily inter-defined (ibid., 79-81). While it’s certainly the case that there is some convention as to how we socially express our biological sex, there is nonetheless no denying that such expression flows out of a real objective ontological reality, one that is determined at the moment of conception (ibid., 149, 78).

We come into the world as sons or daughters—as male or female; and we are thereby disposed toward each other as potential husbands and wives, and thence as potential fathers and mothers (ibid., 159-61). This is the order of things, an order which has God as its source, and which is wrapped up with the very meaning of life. We do grave harm when we seek to work against—not with—the God-given order of nature.

How can we restore a culture of the goodness of the body and its meaning, drawing our moral cues from its objective meaning and purpose? How can we better come to grips with the body God gave us, with its gifts and flaws in all, and ultimately help others to do the same?

You May Also Like:

Bruce Jenner & the Transgender Question (Fr. Mike Schmitz)

How Catholics Can Serve People Who Experience Same-Sex Attraction (podcast)

Coming to Our Senses: Growing Confusion on Gender Identity

About Andrew Swafford

![]() Swafford is Associate Professor of Theology at Benedictine College. He is author of Spiritual Survival in the Modern World: Insights from C.S. Lewis’ Screwtape Letters; John Paul II to Aristotle and Back Again: A Christian Philosophy of Life; and Nature and Grace: A New Approach to Thomistic Resourcement. He is a member of the Academy of Catholic Theology and Society of Biblical Literature; and a senior fellow at the St. Paul Center for Biblical Theology. Andrew has appeared on EWTN’s Catholicism on Campus and is a regular contributor to Ascension’s blog as well as Chastity Project. He lives with his wife Sarah and their four children in Atchison, Kansas.

Swafford is Associate Professor of Theology at Benedictine College. He is author of Spiritual Survival in the Modern World: Insights from C.S. Lewis’ Screwtape Letters; John Paul II to Aristotle and Back Again: A Christian Philosophy of Life; and Nature and Grace: A New Approach to Thomistic Resourcement. He is a member of the Academy of Catholic Theology and Society of Biblical Literature; and a senior fellow at the St. Paul Center for Biblical Theology. Andrew has appeared on EWTN’s Catholicism on Campus and is a regular contributor to Ascension’s blog as well as Chastity Project. He lives with his wife Sarah and their four children in Atchison, Kansas.

Howdy,

We are born either with XX or XY chromosomes(my wife states that Y chromosome is defective X). We are either female or male. Changing physical appearance without changing chromosomes is mutilation as initially done by National Socialist German Workers’ Party doctors. Transgender is “new speak”invented by present day doctors perforning mutilation. These same doctors champion transgenderism as cvill right as opposed to mental illness which it is. We need to treat the illnes versus symptoms through mutilation.

Respectfully,