Here beneath these signs are hidden / Priceless things to sense forbidden; / Signs, not things are all we see: / Blood is poured and flesh is broken, / Yet in either wondrous token / Christ entire we know to be.

Lauda Sion, the Sequence for Corpus Christi

Catholic tradition has often referred to the Eucharist as “the bread of angels.” While true in a certain sense, the Eucharist may more appropriately be called “the bread of God.” For the sacrament of the Most Holy Body and Blood comes from God, contains God, and transforms into God those who eat it.

First, the Eucharist comes from God. He is the “divine baker and vintner,” as it were. Man has had “food issues” from the beginning, ever since Adam and Eve ate of the forbidden tree. Since then, the descendants of Adam have sought to fill themselves on food that does not satisfy and slake their thirst on drink that does not quench. Part of the Father’s “diet plan” for his children begins as the Chosen People journey through the desert. Responding to his people’s wish for the food of their former days, the Lord provides manna:

“In the evening quails came up and covered the camp; and in the morning dew lay round about the camp. And when the dew had gone up, there was on the face of the wilderness a fine, flake-like thing, fine as hoarfrost on the ground.”

Exodus 16:13–14

The Lord also gave water to accompany them along their way to the Promised Land (see Exodus 17:6).

Later, with the coming of Christ, God gives us true bread and true drink—the very Body and Blood of his Son. The Father nourishes us with healthy food and drink by sending his Spirit “like the dewfall” upon mere bread and wine. As God’s new People of God, the Church, we eat divine Bread and imbibe divine Drink on our journey to the “new Promised Land,” heaven.

The Eucharist sustains us on our way because it truly is the Body, Blood, Soul, and Divinity of Jesus. Our belief that we are consuming God himself would be un-believable if God himself, in the person of Jesus, had not asserted it:

“I am the living bread which came down from heaven … [M]y flesh is food indeed, and my blood is drink indeed.”

John 6:51, 55; proclaimed in the Gospel of this solemnity during Year A

Jesus confirms his Eucharistic words at the Last Supper:

“This is my body which is for you … This chalice is the new covenant in my blood.”

1 Corinthians 11:24–25; the second reading at Mass during Year C; also Mark 14, the Gospel reading for Year B

The substance of the Eucharist—that which stands beneath it and fills it with reality—is God himself. “What could be more wonderful than this?” asks St. Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) in the Office of Readings for the day.

Indeed, the Church expresses her wonder about the substance of the Eucharist in the Opening Prayer (Collect) of the Mass for this Solemnity. Unlike nearly every Collect throughout the liturgical year that is addressed to God the Father, the Opening Prayer on the Solemnity of Corpus Christi addresses the Eucharistic Christ himself:

“O God, who in this wonderful Sacrament have left us a memorial of your Passion, grant us, we pray, so to revere the sacred mysteries of your Body and Blood that we may always experience in ourselves the fruits of your redemption.”

But we hear this prayer regularly throughout the year as well. The Church prays this same text prior to Benediction with the Blessed Sacrament that concludes Eucharistic Adoration—she speaks directly to Christ, present before her.

Finally, we know that the Sacrament of the Eucharist is the food of God because of its remarkable effect upon those who receive it worthily. In short: we become what we eat—we become God. St. Thomas Aquinas not only contributed great philosophical and theological insights to our understanding of the Eucharist, but he also penned beautiful poetry celebrating the “sacrament of sacraments,” including Lauda Sion (“Laud, O Sion”), O Salutaris Hostia (“O Saving Victim”), Pange Lingua (“Sing, my Tongue,” a hymn the last two verses of which are sung as the Tantum Ergo), and Sacris solemniis (from which the term “bread of angels” comes). It is no wonder, then, that his words are heard throughout this solemnity.

The Office of Readings, for example, opens with one of his most remarkable lines:

“Since it was the will of God’s only-begotten Son that men should share in his divinity, he assumed our nature in order that by becoming man he might make men gods.”

Make men gods? But was this not the essence of the sin of our first parents— wanting to be gods? The central difference between their desire for divinization and ours depends wholly on who is doing the divinizing: Our first parents sought divinity according to their own designs, but our divinization comes from God’s own will and power. And the Eucharist is one of his means to divinize us, to make us, as St. Thomas says, “gods.”

Like St. Thomas, St. Augustine also saw the human and divine dynamic at work in the Eucharist. “I am the food of grown men,” St. Augustine hears the Eucharistic Christ tell him. “Grow, and you shall feed upon me; nor shall you change me, like the food of your flesh, into yourself, but you shall be changed into me.” (Cited in Pope Benedict XVI’s Sacramentum Caritatis (February 22, 2007), 70.) We really, truly become what we eat! As Pope Benedict XVI says, by the Eucharist we become blood relations, “consanguine,” with Jesus:

“The blood of Jesus is his love, in which divine life and human life have become one.”

Benedict XVI, homily given at the Mass of the Lord’s Supper, 2009

Thus the “bread of angels” is first and foremost the “bread of God.” It comes from him, it is filled with him, and it transforms in him all who receive it worthily. In this way, the Solemnity of Corpus Christi provides for us an opportunity to fill up our lives with God even as we recognize that we need no longer be fed up with the emptiness created by our fallen nature.

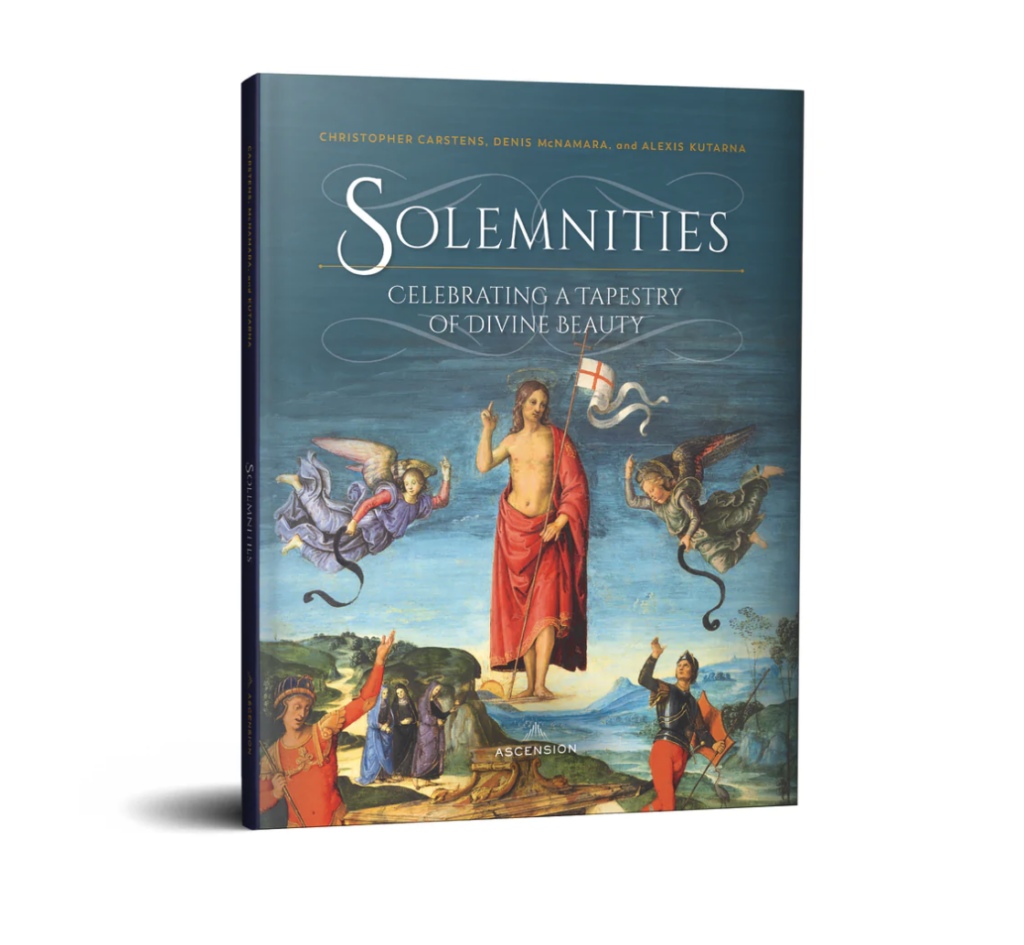

Celebrate the Greatest Feasts of the Catholic Church

A timeless Catholic heirloom, Solemnities: Celebrating a Tapestry of Divine Beauty helps Catholics understand the most important celebrations of the Catholic Faith and why they are important.

This article is an excerpt from Solemnities: Celebrating a Tapestry of Divine Beauty. To learn more about the history, relevant art, and how to celebrate the Solemnities of the Catholic Church, order Solemnities: Celebrating a Tapestry of Divine Beauty.

0 Comments