The Son of Man mourned the death of John the Baptist by seeking solitude on the sea. He wept when Lazarus died. He agonized in the garden. He suffered the Way of the Cross. Although Our Lord rarely displayed anger, biblical accounts relay his sorrow and suffering.

Through Jesus’ passion he carried the world to his Father, and in their suffering, many great holy men and women draw us closer to him.

As Westerners in the modern era, few of us suffer the overt religious persecution endured by the members of Christ’s early Church, but increasingly, anti-Catholic and anti-Christian sentiment has infiltrated modern culture. The novel coronavirus has magnified depression and anxiety, and brought to light some very real suffering. Loss of community, loss of occupation, and loss of life have altered our reality.

While these challenges are unique to our circumstances, they are no less pronounced than the struggles of humankind throughout history. C.S. Lewis said, “God whispers to us in our pleasures, speaks in our consciences, but shouts in our pains. It is his megaphone to rouse a deaf world.” Throughout history, the body of saints has provided guidance, an example, and incredible inspiration in times of darkness. Through trials and suffering, external pressures, and internal conflict, they have risen above earthly circumstances to gain heavenly favor; they have relinquished their deafness to hear God.

St. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross

Edith Stein experienced many dark days on her journey to faith and ultimate joy. The eleventh child born into a devout Jewish family on October 12, 1981, Stein grew up in the eastern reaches of the German Empire, what is modern-day Poland. She lost her father at a young age and gradually lost her faith, replacing it with the religion of academia. Stein devoted herself to women’s issues while studying at the University of Breslau, referring to herself as a “radical suffragette.”

Stein began work as an assistant to Edmund Husserl, a widely acclaimed philosopher, in 1913 at Gottingen University. This prestigious position, and interactions with the philosopher Max Scheler, would lay the groundwork for Stein’s later conversion to Catholicism. But before then, she would experience intense depression.

Serving in an Austrian field hospital during the dark days of World War I, she viewed the deterioration of young soldiers in the typhus ward, and despite her numerous academic accolades, Stein was often turned away from teaching positions due to her gender. An accumulation of wartime experiences and professional rejection would further her despondence, causing her to once write, “I gradually worked myself into real despair…I could no longer cross the street without wishing that a car would run over me…and I would not come out alive…”

She continued her studies after the hospital closed, acquiring a doctorate summa cum laude in 1917. Her thesis “The Problem of Empathy,” concluded that, “there have been people who believed that a sudden change had occurred within them and that this was a result of God’s grace.” Stein continued to work toward understanding the human condition and through her devotion to that study, she was coming to the realization of true faith. “My longing for truth,” she would later write, “was a single prayer.”

Then came a moment that, according to Stein, would redirect her course more resolutely. Visiting a recently widowed friend, she was met with Christian hope and joy. She felt inspired. Humanity, she witnessed, was only a journey home. Reading the autobiography of St. Teresa of Avila furthered her conviction.

From darkness to daylight, as a daughter of the Carmelite order, Stein would teach and lecture on the faith. Giving meaning to those trapped in mental darkness, she advised that, “there is no chance and that the whole of…life, down to every detail, has been mapped out in God’s divine providence…” She believed her dark days led her to her true calling.

Stein championed the small moments and beauty of motherhood and service as a woman and emptying of oneself to gain fulfillment and joy. She would continue to serve, teach, and write until her death as a martyr in Auschwitz on August 9, 1942.

Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen

A man of the modern era, Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen embraced a changing world, utilizing progressive technological tools to illuminate and celebrate the ancient tradition of the Catholic Faith.

Born Peter Sheen on May 8, 1895, to a farmer and his wife, Sheen was raised in a traditionally Catholic home in rural Illinois. As with Stein, Sheen devoted himself to his studies. His thirst for truth and study of the Catholic faith drew him from humble beginnings. His study of human nature through theology, philosophy, and religious studies was continuously shared and communal. Delivering lectures and sermons years before he became a hallmark radio host, Sheen unabashedly shared and discussed the faith. Though he studied the internal, he lived externally, sharing his gifts and understanding.

This would lead Sheen to his ultimate fame as a television host. His series Life Is Worth Living, on The Catholic Hour radio program would win him an Emmy and showcase Catholicism to the world in a way it had never been on display before. For the twenty years following his guest spot in 1930, Sheen never shied away from the conflicts of the world. Social strife and morality in the tradition of Thomas Aquinas were foundational to Sheen’s messaging.

Recognizing a social culture of disillusionment, Sheen may not have experienced depression personally, but he recognized its base and spoke on it. In Peace of the Soul, Sheen writes, “Depression comes not from having faults but from the refusal to face them. There are tens of thousands of persons today suffering from fears which in reality are nothing but the effects of hidden sin. The examination of conscience will cure us of self-deception. It will also cure us of depression.”

Sheen responded to the call for service to the point of physical exhaustion. He wrote of giving personal attention to 75-100 letters a day, preparing for a ceaseless string of lectures and never missing an opportunity to serve. “If you cannot reason yourself into the meaning and the purpose of life, you will act yourself into the meaning and purpose of life,” he said.

Though Sheen committed an hour each day to the veneration of the Blessed Sacrament, he spent the majority of his days studying. His success in evangelizing was driven by relentless service to his calling. He died December 9, 1979.

St. Teresa of Calcutta

Macedonian born Agnes Gonxha Bojaxhiu would experience deep bouts of depression over her life, but her vigor to serve never diminished. Known worldwide as “Mother Teresa,” Bojaxhiu was born into relative comfort in the capital city of Skopje in 1910. Her devout Roman Catholic family benefitted from her father’s success as an entrepreneur and lived well until her father’s sudden death in 1919.

Her mother remained remarkably charitable following the family crisis, opening her home to the hungry even as the young family faced financial struggles. Her actions left an indelible mark on the young Agnes, who would one day found the Missionaries of Charity.

At the age of 18, Agnes followed the call to religious life to Dublin, Ireland, where she would join the Sisters of Loreto. A year later, as a novice, she would be sent to Darjeeling, India, to teach girls from low-income families. She excelled in her assignment, mastering Bengali and Hindi and devoting her energy to drawing her students to Christ. “Give me the strength to be ever the light of their lives, so that I may lead them at last to you,” she would write.

In 1944, she became the school’s principal, but unexpectedly, she would request to break her vow of obedience to her order two years later to adhere to a “call within a call.” Riding a train to the Himalayan foothills for a retreat, Agnes would hear Christ’s voice calling her to minister to the destitute and sick in the slums of Calcutta.

Living among the poorest of the poor, Mother Teresa began her work with a familiar endeavor—opening a school. She would follow that with a home for the dying and further the work with the establishment of a leper colony, orphanage, family clinic, and mobile health clinics. Her fearless service inspired global attention and funded ministries to the poor and sick across the world.

Mother Teresa’s Missionaries of Charity created 610 foundations in more than 120 countries worldwide by the time of her death in 1997. The Missionaries of Charity included more than 4,000 members. St. Teresa’s impact was incredible, and yet she experienced years of intense, spiritual darkness—a fear that God had abandoned her.

Published posthumously, Come Be My Light, a collection of her personal writings, would reveal a deep feeling of separation from God, one that would haunt the saint for nearly fifty years. Though she navigated the political, social, and cultural intricacies of her mission with determination and ease, her writings revealed a spiritual desert; a revelation that would baffle her admirers.

Though human nature is prone to self-centeredness, St. Teresa outpoured herself. The paradox of her suffering drove her persistence. She ministered to the sick, the poor, the weak, the hungry, the naked, and in doing so, served Christ, held Christ, fed Christ, clothed Christ. In walking the streets of Calcutta, in carrying the burdens of the poor, so too could she share in Christ’s cross.

In nearly five decades, the saint would only record one brief reprieve from this interior struggle. When Pope Pius XII died in 1958, a requiem Mass was celebrated in the Calcutta cathedral. Attending the service, Teresa wrote, “Today my soul is filled with love.” The pontiff had approved her mission in the slums and the saint would see this as proof that God had indeed called her to the work.

In an excerpt from her book, St. Teresa of Calcutta: Missionary, Mother, Mystic, Kerry Walters, writes, “So it was perhaps inevitable, given that she shared in the suffering of the people she served, that Teresa would eventually discern her own inner poverty as a share in the suffering of Christ himself. She remembered the oath she’d made back in 1942 never to deny God anything asked of her, and she realized that loyalty to the oath meant embracing God’s withdrawal.” She died September 5, 1997, her final words, written on paper, “I want Jesus.”

St. Pope John Paul II

Karol Wotjyla was born May 18, 1920, in a Poland overshadowed by the widespread destruction of Europe during the first World War. A boy who would become pope, St. John Paul II was known for his central place in international conflict—a man who would stand up to communism and the widespread quelling of religious expression during the Cold War, a champion of Vatican II, and a world traveler, beloved and welcomed across nations.

But before he was a pope, Wotjyla was a boy who suffered great personal loss. His mother, a devout Roman Catholic, died when he was eight years old. The loss of his only sibling, Edmund, an older brother who contracted scarlet fever in the hospital where he worked as a doctor, furthered his suffering. Forced to abandon traditional studies under the communist regime that overtook Poland, Wotjyla labored in a quarry to support himself and his father, who would die of a heart attack in 1941. At just twenty-one years of age, Karol was left with no family. He would turn to lean heavily on his faith, finding light in darkness, “spiritually uniting himself to the Cross of Christ,” and grasping the, “meaning of suffering” (Salvifici Doloris).

In Salvifici Doloris, published February 1984, Wotjyla wrote, “For it is above all a call. It is a vocation…He does not discover this meaning at his own human level, but at the level of the suffering of Christ. At the same time, however, from this level of Christ the salvific meaning of suffering descends to man’s level and becomes, in a sense, the individual’s personal response. It is then that man finds in his suffering interior peace and even spiritual joy.”

As his call to the priesthood became clearer, Wotjyla would undertake further hardship as communist persecution of religion bled into 1940s Poland. As he writes in Rise, Let Us Be on Our Way, “God’s love does not impose burdens upon us that we cannot carry, nor make demands of us that we cannot fulfill. For whatever He asks of us, He provides the help that is needed.”

As pope, St. John Paul II acknowledged mental suffering as an opportunity to grow spiritually, a “mystery” that could lead caregivers to great kindness and compassion and the sufferer to new growth. In his address to participants in the 18th International Conference on the theme of Depression, Pope St. John Paul II described the illness of depression as involving a, “crack, or even fracture in social, professional or family relationships.”

“In his infinite love, God is always close to those who are suffering. Depressive illness can be a way to discover other aspects of oneself and new forms of encounter with God. Christ listens to the cry of those whose boat is rocked by the storm.”

The stormy seas, as calmed by our Lord (Mark 4:35-41), called for little more than the asking by his disciples.

Hope, Service, Action, Community

Though he mourned John the Baptist, Jesus returned to land and fed five thousand.

Though he wept for Lazarus, he brought him out of death to life.

Though he agonized in the garden, he offered himself willingly on the Cross. From the great suffering of that Cross came the Resurrection. There is a light at the end of darkness, and as Pope St. John Paul II said, “We are an Easter People.”

Great saints faced hardship and depression with service and action, surrender and hope. In a culture overwhelmed by the material, they were able to attain spiritual riches.

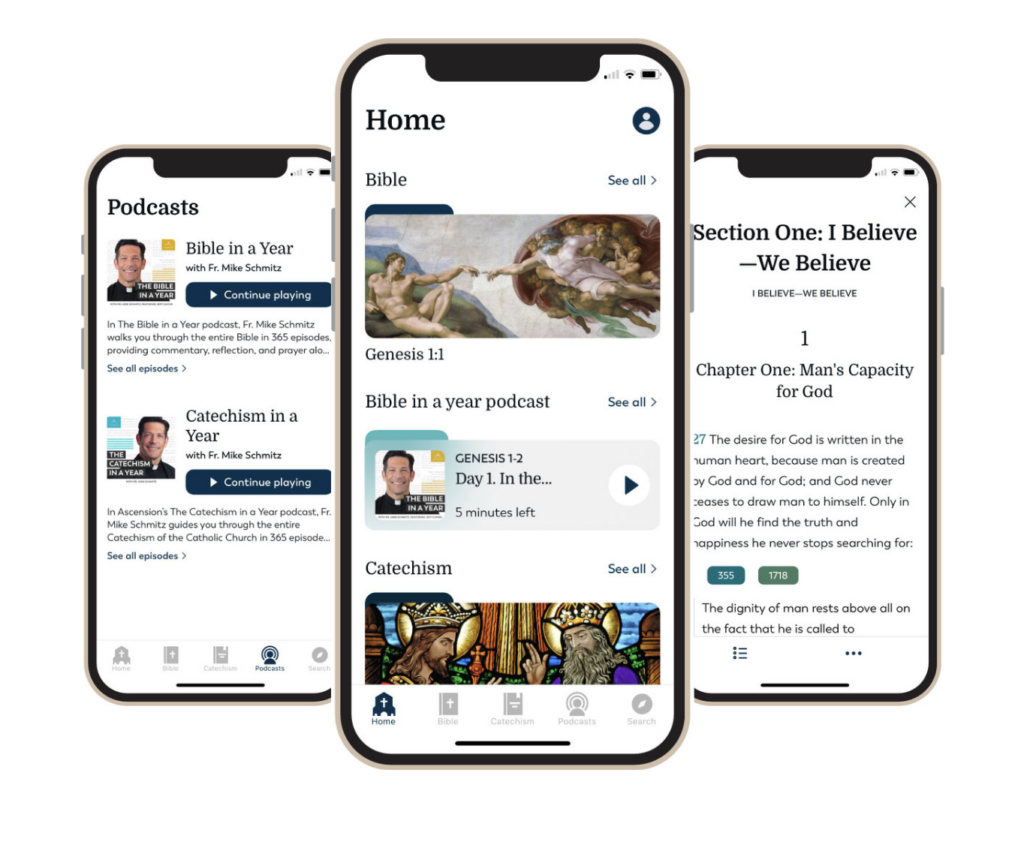

It’s Here: The Bible & Catechism App!

The word of God and the complete teachings of the Catholic Church. Answers and commentary by Fr. Mike Schmitz, Jeff Cavins, and other experts. Video, audio, and textual commentary. Right on your phone.

You May Also Like:

Depression, Sexism in the Church, Candy During Lent, and Posting on Facebook [Audio]

Raise Your Expectations: How Saints Live Differently [CFR Video]

Engaging the Saints and Angels [Audio]

Ashley Bateman is a policy reform writer for The Heartland Institute and contributor to The Federalist. Her work has been featured in The Washington Times, The Daily Caller, The New York Post, The American Thinker, and numerous other publications. She previously worked as an adjunct scholar for The Lexington Institute and as editor, writer and photographer for The Warner Weekly, a publication for the American military community in Bamberg, Germany.

Ashley is a board member at a Catholic homeschool cooperative in Virginia. She homeschools her four incredible children along with her brilliant, engineer/scientist husband, who is a convert to the Catholic Faith. She is an aspiring gardener, traveler, lifelong learner, and, foremost, a disciple of the Catholic Faith.

This was an infomative, inspiring piece.

Thank you for sharing your knowledge with me.